When I first arrived in New Zealand I was told a story – the story that the North Island was actually a giant fish. The story turned out to be slightly true.

Maui, a Polynesian demi-god and his brothers went fishing and Maui took them further out into the ocean than they’d ever been. He cast his line into the sea and in the murky depths it hooked on something. Something big.

Maui tried to haul in the line and sea became turbulent and began to boil. The giant fish fought but wasn’t as strong as Maui. Maui brought the thrashing fish to the surface and today the fish of Maui, Te Ika a Maui, is the North Island of New Zealand.

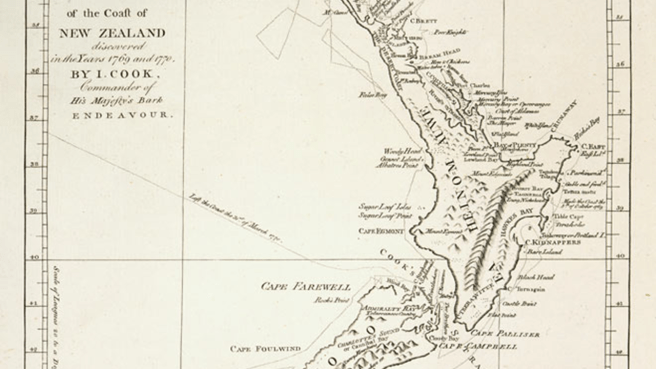

Is the story true? Well, if you look at the North Island from the right angle, it does look a bit like an enormous stingray.

There is one part of the story that doesn’t ring true. Ancient Polynesians were accomplished navigators. They navigated by the stars; they understood the wind, tides, and currents. But they didn’t have maps. And it’s very difficult to see the North Island from just the right angle to make the stingray connection.

Chances are the first person to see the full shape of the North Island was Captain Cook, who charted the coast of New Zealand in 1770.

This is disappointing. It’s starting to look as if not only is the fish story not true, but that it must have been made up after first contact with Europeans.

However, the shape of the North Island is not so much a stingray, as a red herring.

It turns out that Maui was a busy chap. In Fished Up or Thrown Down, Patrick Nunn describes the extent of the fishing up myths. Polynesians spent three thousand years colonising the Pacific. In that time, Maui and his father, Tangaroa, god of the sea, fished up dozens, if not hundreds of islands across the Western Pacific and across the Polynesian triangle. The story has been circulating for centuries and the shape of the islands has nothing to do with it.

Stories of Maui’s battle with his catch often tell of a churning, boiling sea.

A Tongan version of the story told by chief Ma’afu in Tales from Old Fiji explains

Pulling on the line, they were aware of something very heavy that the hook had caught.

“Truly a monster of a fish is here!” said one, as they tugged and strained.

“What can it be?” cried another.

“It is no fish, for it makes no struggle,” said a third.

But then the waters rose bubbling and foaming around the canoe, and smoke came from them with a thunderous rumble and roar, and the gods cried out in deadly fear.

The turbulence and smoke are the first glimpse of the truth behind the myth.

The account of the raising of Tonga, according to Lorimer Fison in the preface to Tales from Old Fiji, “suggests volcanic action.”

“In some places in the Pacific, the summits of active volcanoes lurk just a few tens of metres beneath the water’s surface,” says Nunn in On the Edge of Memory. “When these volcanoes periodically erupt, the forced mixing of cold ocean water and liquid rock (heated to perhaps 1,000°C/1,800°F) makes for memorable (phreatomagmatic) explosive eruptions.”

“The thrashing of the fish as it was being hauled from the water agitated and discoloured the ocean surface, just as happens during such shallow-water volcanic eruptions.”

What seems like a small descriptive detail in the story is the faint memory of a real event.

Then the gods shouted, pulling with a mighty will; and from the midst of the waters rose a land, mountain after mountain, till there were seven mountains in all, with valleys between, and flat lands lying at their feet.

When the thrashing fish is finally brought to the surface, the result is spectacular.

We’re very good at picking patterns out of clouds. It doesn’t take too much imagination to see the tail of a huge fish in the vast plume of ash and steam from an undersea eruption.

Fishermen worldwide are great storytellers but no exaggeration is needed to sell this experience. It really was this big.

The giant-fish-equals-volcanism motif is suggestive, but is it real. Compare the map of islands fished up by Maui and Tangaroa with the map below.

This map, also derived from Fished Up or Thrown Down, shows shallow-water volcanoes that have erupted in the last 3,000 years. In that paper, Nunn expands on the idea that the fishing up myths first appeared in Tonga and were reinforced wherever Polynesian explorers came across other shallow-water volcanoes.

Could it all be coincidence? Most of these islands are volcanic. Most of these islands have fishing-up myths. Maybe there’s no more to it.

But the myths contain details that hint at more of the story.

This is a view towards Mt Taranaki on the west of New Zealand’s North Island. The hills in front of it are not volcanic vents; they’re debris heaps left behind when the side of the mountain collapsed. When the volcano erupts, it gets bigger but the rock can be unstable and the mountain collapses, sending out an avalanche of rock across the land in front of it.

The debris heaps are visible here because Taranaki is on land. When shallow-water volcanoes do this, the eruption might create an island that disappears back under the sea soon after.

These “jack-in-the-box” islands are common in Tonga. Fonuafo’ou, the island that’s probably depicted in the lithograph above, has appeared and disappeared several times in the last 200 years.

In some versions of the Maui myth, Maui chooses a fishing spot where land is already visible below the surface. In some versions, the fishing line breaks and the fish slips back under the sea.

Many other myths suggest a history of earthquakes and floods, sea level rise and sea level fall.

The North Island might not actually be a giant stingray, but the myth of Maui is not a complete fabrication either.

We have so much literature available to us, we forget that most of human history was never written down. Ancient events are passed down orally, recorded under layers of story.

A story of superhuman heroes and gargantuan animals turns out to contain more truth than seems likely. A fishy tale contains clues to the real geographic origins of the lands colonised by the people of the Pacific.

References

Fison, L. (1907). Tales from Old Fiji. London: Moring.

Gossage, P. (2016). Maui and other Maori Myths. Auckland: Puffin.

Nunn, P. (2001). On the Convergence of Myth and Reality: Examples from the Pacific Islands. The Geographical Journal, 167(2), 125-138. Retrieved May 27, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/3060483

Nunn, P. (2003). Fished up or Thrown down: The Geography of Pacific Island Origin Myths. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 93(2), 350-364. Retrieved May 27, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1515562

Nunn, P. (2018). The Edge of Memory. London: Bloomsbury.

I have something that is going to completely shock you, leave you rolling your eyes or intrigued to learn more about this ancient time. I have loved tales of dragons and dinosaurs and ancient history ever since I was a child. Ive always wanted to know if they were real and one question most people ask is ” If these animals are real where are their bodies?” Well remember everything dies eventually and those beasts of old have died. HOWEVER I have made a discovery recently that proves undeniably these animals of the mega fauna age did live. Further more their fossilised remains are still easy for anyone to see if you know where to find them so dont take my word for it but the following is a list of animals that are still literally under our noses. The Norse mythology of the Giant sting ray is actually Iceland. Look closely and see all the anatomy is completely intact including the spines that travel up its tail to its back. Also you have missed the Hafgufa. Located at the top of Russia, perfectly preserved fossil of a giant fish covered in armor like scales. He is now the Island Novaya Zemlya an ancient fish once mistaken by mariners as an Island. Ans most significantly, Leviathans remains. His body looks exactly like a dragon measuring over 14 000 kilometers in length in his decayed state. Go to google Earth as you have done and you can see every single detail of his body stretching from the right hand side of Wake Island and his tail ends just of the chilean coast line. Look closely at the perfectly preserved spine and tail resting on the ocean floor also his pectoral fins which measure 2000 kilometers from the top of his back to the tip. Oh! and also I have found Kraken. One tentacle measures over 11 000 kilometers in length. Before Australia existed, there was a giant octopus that was known the world over, because that is literally how large he grew. The Kraken. The stories became myth when he ceased to be but these are his remains now fossilised dead and gone. His body is Australia. No joke. Remove the labels from google earth turn Australia upside down and start from the new zealand tentacle, or the tentacle of Papua new guinea, Or the tentacle that stretches to the Andaman Islands. All the tentacles are intact bar one that has been severed. The largest octopus on earth and no one noticed it. You can see the suction pads, the bone structure running through the tentacles in places as well as the perfectly preserved outline of the body as it decayed on the sea floor. The earth is literally made of Giants. the sea floor is littered with fossils you can see from space. And the Moeraki boulders which are attached to tendonous tissue in muscle is in fact the macroscopic remnants of what lies beneath the flesh of this gargantuan animal. every ball is attached to a tendon. Thos balls have nerves beneath them whis control the octopus ability to use its arms. Look at athe anatomical xrays of the tissue in an octopus and I can promise you I am 100% right. Happy fossil hunting.

LikeLike